An autosomal dominant genetic disorder, type 5 spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA5), occurs in multiple descendants of one paternal uncle and one paternal aunt of President Abraham Lincoln. It has been suggested that Lincoln himself had the disease and that his DNA should be tested for an SCA5-conferring gene. Herein, I review the pertinent phenotypes of Lincoln, his father, and his paternal grandmother and conclude: (1) Lincoln's father did not have SCA5, and, therefore, that Lincoln was not at special risk of the disease, (2) Lincoln had neither subclinical nor visible manifestations of SCA5, (3) Little evidence suggests SCA5 is a "Lincolnian" disorder, and (4) Without additional evidence, Lincoln's DNA should not be tested for SCA5.

IntroductionIn 1994 Ranum et al [1] reported that an autosomal dominant disorder, type 5 spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA5) (OMIM 600224), occurred in 56 of 170 examined descendants of President Abraham Lincoln's paternal grandparents.

Ranum's group [1],[2] hypothesized that Lincoln may himself have had SCA5 because: (a) he had a 25% "prior probability" of inheriting the disease-causing gene variant from a grandparent, (b) his age at death, 56, was within the range of disease onset seen in the kindred, (c) his gait was unusual and, according to one eyewitness, "shambling," and -- contradictorily -- (d) "if President Lincoln had inherited the ataxia gene, his symptoms could have been very mild or as yet undeveloped at the time of his death."[1]

Because the gene causing SCA5 has been identified,[2] DNA testing could definitively diagnose Lincoln. Ranum has declared intent to "pursue a DNA test if the opportunity arose."[3] Others support this.[4]

Arguably, however, DNA testing is justified only when a detailed review of Lincoln's phenotype establishes a sufficiently high probability of having SCA5. Because no such review has been performed, I herein assess the probability that Lincoln had SCA5, based on a recent compilation of primary source materials describing the physical status of Lincoln and his first-degree relatives.[5],[6]

SCA5 in the Lincoln kindredTwo of Lincoln's paternal relatives -- his uncle Josiah and his aunt Mary -- have descendants with SCA5 (Fig. 1). In this kindred, initial symptoms of SCA5 -- gait disturbance, dyscoordinated upper limbs, and slurred speech -- have appeared from ages 10-68, but typically from 20-40.[1]

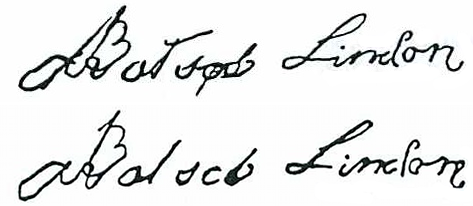

Ranum et al [1] postulate that one of Lincoln's paternal grandparents had SCA5. Because of two signatures (Fig. 2A), his grandmother, Bathsheba Herring Lincoln, has drawn the greater interest. Handwriting experts at the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation reported that her penmanship "demonstrated characteristics that may be caused by a lack of coordination, a mental or physical impairment, a poor writing skill level, the writing surface or writing instrument, drug or alcohol effects, or the hand position of the writing."[7]

Citing her privileged upbringing, Nee and Higgins [7] dismissed the possibility of poor writing skills. They also dismissed transient impairment, because the two signatures, penned 18 months apart, have similar appearance. Therefore, they suggested SCA5 as the most likely cause, and Bathsheba Lincoln as the source of the SCA5 gene in the Lincoln kindred.

Several observations weaken these conclusions: (1) Bathsheba's consistent mis-spelling of her last name is direct evidence of poor literacy: in both signatures, the misplaced second "L" cannot be attributed to ataxia because the connection from "O" to terminal "N" is smooth and clearly intended. (2) In both signatures, the dot over the "i" is perfectly placed, which would be difficult in ataxic writing. (3) If ataxia adds random motion to handwriting, the signatures should be significantly different, but they are remarkably similar, even in small features, e.g. the terminal curl on the terminal "N," the shepherd's crook atop the second "L," and the unusual flourish before the "B." (4) Despite some tremulousness in the initial "B," the letters have predominantly smooth strokes, without abrupt irregularities.

Given these doubts, it cannot be presumed that Bathsheba Lincoln had SCA5.

SCA5 in President Lincoln's fatherIf President Lincoln inherited an SCA5-conferring gene from a paternal grandparent, it would have passed through his father, Thomas.

No abnormalities in Thomas's gait are known,[6 ¶¶5119ff] except for walking slowly and, in one account, "surely."[8 p149] Twice after boating down the Mississippi River, he walked from New Orleans back to Kentucky or Indiana[8 p102] -- about 700 miles. At least one trip occurred past age 40.[8 p439n]

Just before turning 71, Thomas wrote his son, asking for money. Although exaggerated physical infirmity would have aided his begging, Thomas instead wrote: "I and the Old womman [sic] is in the best of health."[9 p114] This would imply his arms and legs functioned normally.

Thomas Lincoln died a farmer at age 73, i.e. past the oldest age at which SCA5 symptoms appear in the Lincoln kindred. He died "after suffering for many weeks from a disorder of the kidneys."[10 p60] In multiple biographical interviews, his friends never mention invalidism.[8],[11]

Thus, it appears that Lincoln's father was never ataxic, and that he had no SCA5 gene.

President Lincoln's Upper Limb FunctionThe handwriting of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) has not been studied systematically. It appears, however, that external factors had the largest influence on his penmanship.

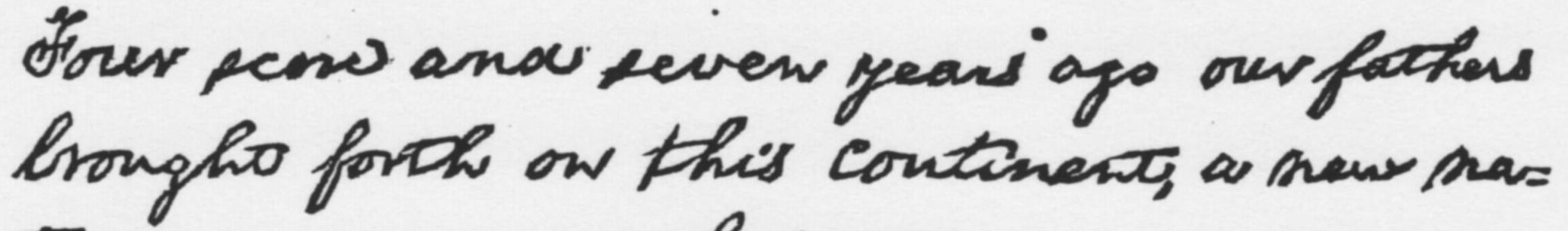

Famously, he signed the Emancipation Proclamation after an hours-long handshaking session, and took pains to keep his signature steady.[12 p407] Weeks later, in February 1863, his hand trembled in writing a note, but this was probably part of a larger medical issue, given that the witness described him as "feeble," "worn," and "haggard."[13 p417] Later that year Lincoln drafted the Gettysburg Address in neat script.[14] His script was even neater in a March 1864 presentation copy (Fig. 2B).

Lincoln's handwriting strongly militates against upper limb ataxia.[7]

President Lincoln's GaitAs evidence of ataxia, Ranum et al [1] cite an 1861 article by reporter William Russell. Russell said Lincoln had "a shambling, loose, irregular, almost unsteady gait."[15 pp37-38] His writing style must, however, be considered.

Russell's colorful article also mentioned Lincoln's "thatch of wild, republican hair," his "flapping and wide projecting ears," and his "straggling" lips.[15 pp37-38] Four months later, Russell saw Lincoln on the street, "striding like a crane in a bulrush swamp."[15 pp428-429] Thus, Russell's word, "shambling," cannot be accepted as clinically precise.

Other accounts of Lincoln's gait [6 ¶¶1022ff] label it unusual, but never unsteady. One witness said the walking President looked as if "he was about to plunge forward, from his right shoulder, for he always walked, when he had anything in his hand, as if he was pushing something in front of him."[16 p321] Another noted Lincoln's "peculiar swinging gait."[13 p373] William Herndon, Lincoln's 16-year law partner, left a detailed description:

When he walked he moved cautiously but firmly; his long arms and giant hands swung down by his side. He walked with even tread, the inner sides of his feet being parallel. He put the whole foot flat down on the ground at once, not landing on the heel; he likewise lifted his foot all at once, not rising from the toe, and hence he had no spring to his walk. His walk was undulatory -- catching and pocketing tire, weariness, and pain, all up and down his person.[10 pp471-472]

Even more brilliantly, attorney Ward Lamon observed that Lincoln "never wore his shoes out at the heel and the toe more, as most men do, than at the middle of the sole; yet his gait was not altogether awkward, and there was manifest physical power in his step."[17 p470]

Eyewitnesses describe Lincoln bounding up steps two and three at a time in 1856 and 1860.[8 pp407, 734],[18] Others noted Lincoln's fast walking pace in 1830[8 p90] and in 1860:

... taking immense strides, [with a] carpet-bag and an umbrella in his hands, and his coat-skirts flying in the breeze. ... [His] head craned forward, apparently much over the balance, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, [he] was moving something like a hurricane across that rough stubble-field! He approached [a] fence, sprang over it as nimbly as a boy of eighteen, and disappeared from my sight.[18]

In 1864 the White House stables caught fire. Lincoln ran to them at a "dog trot" -- almost a "dead run" for his guard.[16 p235] Once outside, Lincoln "leapt over a hedge and flung open the stable doors to get the animals out."[19]p297]

Lincoln famously walked long distances in childhood and young adulthood,[6 ¶¶1032ff] including a 200-mile round-trip in his 20s.[8 p597] As late as February 1864 he would rather walk a mile than wait for a tardy carriage.[20 p175]

I found no statements that Lincoln's gait changed over time.

Lincoln's lower limb controlSubcinical abnormalities of lower-limb control may exist before gait abnormalities become visible to observers.

Among the anecdotes illustrating Lincoln's normal, or perhaps superior, ability to control his legs,[21 p48],[22 p244] the most remarkable occurred when Lincoln visited an Army encampment in May 1862. General Irvin McDowell showed him a wide ravine, 100 feet deep, with a long bridge above it. Still under construction, the bridge was only one plank wide. Lincoln suddenly said, "Let us walk over," and did. The Secretary of War followed, but halfway across became dizzy and stopped. He was rescued by an admiral, who was himself rather giddy.[23 p369]

President Lincoln's VoiceAlthough Lincoln had a high-pitched voice that would become shrill when he was excited, none of the dozen or so written descriptions of his voice mention anomalous enunciation or pitch unsteadiness compatible with ataxic speech.[6 ¶¶3698ff] To the contrary, at Gettysburg in 1863 Lincoln spoke in "clear, ringing, earnest tones,"[24 p252] and at his second inaugural, six weeks before he died, "every word was clear and audible ... over the vast concourse."[25 p239]

Is "Lincoln Ataxia" a Misnomer?If Bathsheba, Thomas, and President Abraham Lincoln were free of SCA5, then all cases of SCA5 reported by Ranum et al [1] apparently derive from two unnamed persons in generation V (Fig. 1). In both cases, however, no data show that the Lincoln-descendant -- as opposed to their spouse -- had SCA5.

It is, therefore, more accurate to say the first two SCA5 cases lie within two breeding pairs in generation V.

Although these two breeding pairs have common Lincoln ancestors, it would hardly be surprising to find them sharing other common ancestors. Classically, these four individuals would descend from 120 (i.e., 8+16+32+64) members extending back to generation I. This large number offers much opportunity for commonalities, especially given the small American frontier population of the 1700s and 1800s, and the tendency of pioneers to stably congregate in family groups.[21 p11]

Mathematically, it seems likely that a non-Lincolnian common ancestor introduced SCA5 to the lines of Josiah and Mary. Together, Josiah and Mary had eight children and >27 grandchildren,[26] yet among their uncounted great-grandchildren, only two cases of SCA5 are inferred. While just two cases among the great-grandchildren is certainly possible, the likeliest outcomes of simple autosomal dominant inheritance would yield far more. Moreover, the Indiana Lincolns, of which Josiah's line was a major part, "were generally hardy and rugged."[11A]

DiscussionSCA5 occurs in descendants of President Abraham Lincoln's paternal grandparents.[1] Although historical diagnoses are always uncertain, strong conclusions about the Lincolns are possible.

First, the President's father had no SCA5 symptoms. Because he lived years past the latest age at which symptoms develop, it may also be concluded that Lincoln's father did not carry an SCA5 gene and, therefore, that President Lincoln was not at special risk for the disease.

Second, nothing in President Lincoln's phenotype suggests SCA5. Even into his last years, his lower limbs, upper limbs, and voice showed no evidence of ataxia. He lived far past the ages when SCA5 symptoms typically appear, though not past the latest such age. The remarkable bridge-crossing incident effectively rules out subclinical ataxia.

Lincoln's gait was unusual, but not ataxic. No evidence suggests it changed over time, as it would in SCA5. Other diagnoses should be considered.[6 ¶¶1060,1083] Because Lincoln bore many musculoskeletal stigmata of Marfan syndrome,[5 pp44-85, 185-193],[27],[28] orthopedic or myopathic factors may have influenced his gait. For example, his great toes were exceedingly long.[5 pp64ff],[19 pp46-47, 97-98, 291] Perhaps this limited forefoot flexibility, leading to a flat-footed gait.[5 p71]

Despite a 1997 call to discard the term,[7] SCA5 continues to be called "Lincoln ataxia."[29] If, as suggested herein, Lincoln's grandmother did not have SCA5, then the evidence that SCA5 occurred in the Lincoln kindred before generation V is weak, consisting only of the fact that a common Lincoln ancestor unites two lines of SCA5 cases documented to begin four generations later.

The present analysis yields several recommendations: (a) future reports mentioning SCA5 in the Lincoln family should express significant uncertainty that the disease affected any Lincoln member before generation V, (b) any mention of President Abraham Lincoln and SCA5 should reflect skepticism that he had the condition, (c) because SCA5 in President Lincoln is so unlikely on clinical grounds, his DNA should not be analyzed for SCA5-related genes, (d) SCA5 should not be called "Lincoln ataxia," and (e) non-Lincolnian common ancestors of the SCA5 cases should be sought.

References

- 1. Ranum LPW, Schut LJ, Lundgren JK, Orr HT, Livingston DM. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 5 in a family descended from the grandparents of President Lincoln maps to chromosome 11. Nat Genet. 1994; 8: 280-284.

- 2. Ikeda Y, Dick KA, Weatherspoon MR, Gincel D, Armbrust KR, Dalton JC, Stevanin G, Durr A, Zuhlke C, Burk K, Clark HB, Brice A, Rothstein JD, Schut LJ, Day JW, Ranum LPW. Spectrin mutations cause spinocerebellar ataxia type 5. Nat Genet. 2006; 38: 184-190.

- 3. Forliti A. Disease may have caused Lincoln's gait. Associated Press. January 28, 2006.

- 4. Hirschhorn N. Greaves IA. Lincoln's gait. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2006; 49: 631-632.

- 5. Sotos JG. The Physical Lincoln. Version 1.1. Mt. Vernon, VA. Mt. Vernon Book Systems, 2008.

- 6. Sotos JG. The Physical Lincoln Sourcebook. Version 1.1. Mt. Vernon, VA. Mt. Vernon Book Systems, 2008.

- 7. Nee L, Higgins JJ. Should spinocerebellar ataxia 5 be called Lincoln ataxia? Neurology. 1997; 49: 298-302.

- 8. Wilson DL, Davis RO (eds). Herndon's Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements about Abraham Lincoln. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

- 9. Randall RP. Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage. Boston: Little, Brown, 1953.

- 10. Herndon WH, Weik JW. Herndon's Life of Lincoln. Cleveland: World Publishing, 1942.

- 11. Murr JE. "Lincoln in Indiana." (Three parts.) Indiana Magazine of History. (A) 1917 Dec.; 13(4): 307-348. (B) 1918 March; 14(1): 13-75. (C) 1918 June; 14(2): 148-182.

- 12. Donald DH. Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster/Touchstone, 1996.

- 13. French BB, Cole DB & McDonough JJ (eds). Witness to the Young Republic: A Yankee's Journal, 1828-1870. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1989.

- 14. Nicolay JG. Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. The Century Magazine. 1893-1894; 47: 596-608.

- 15. Russell WH. My Diary North and South. Boston: T.O.H.P. Burnham, 1863.

- 16. Kunhardt PB Jr, Kunhardt PB III. Kunhardt PW. Lincoln: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

- 17. Lamon WH. The Life of Abraham Lincoln; from His Birth to his Inauguration as President. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1872.

- 18. Volk LW. The Lincoln life-mask and how it was made. The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. December 1881; 23(2): 223-228.

- 19. Kunhardt DM, Kunhardt PB. Twenty Days: A Narrative in Text and Pictures of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Twenty Days and Nights that Followed. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.

- 20. Ostendorf L. Lincoln's Photographs: A Complete Album. Dayton, OH: Rockywood Press, 1998.

- 21. Whitney HC. Lincoln the Citizen: Volume One of a Life of Lincoln. New York: Baker & Taylor, 1908.

- 22. Burlingame M (ed.). Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997.

- 23. Dahlgren MV. Memoir of John A. Dahlgren, Rear-Admiral United States Navy. Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1882.

- 24. Carr CE. My Day and Generation. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1908.

- 25. Brooks N. Washington in Lincoln's Time. New York: The Century Co., 1896.

- 26. Lincoln W. History of the Lincoln Family: An Account of the Descendants of Samuel Lincoln of Hingham, Massachusetts 1637-1690. Worcester, MA: Commonwealth Press, 1923.

- 27. Gordon AM. Abraham Lincoln -- a medical appraisal. J Ky Med Assoc. 1962; 60: 249-253.

- 28. Schwartz H. Abraham Lincoln and the Marfan syndrome. JAMA. 1964; 187: 473-479.

- 29. National Ataxia Foundation. 2005 annual report. Minneapolis. Accessed online on 11 May 2009 at: http://bit.ly/14OFu9H

- 30. Lea JH, Hutchinson JR. The Ancestry of Abraham Lincoln. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1909.